It is increasingly clear that China’s economic and political power rivals that of the US. This is potentially a serious problem for multinational companies, since China’s rise could lead to more US–China trade conflict and disruption of supply chains, threatening new and ongoing foreign direct investment, and drawing other countries into the jostling for power. However, we argue that globalization is not necessarily endangered by China’s emergence as a comparable power to the US. The US and China both have vested interests in maintaining the open economic order, and these two countries are each providing the global public goods that incentivize economic openness among other countries of the world. In this paper, we develop a theory corresponding to this argument and provide evidence that globalization has not declined even as the global distribution of power has shifted. While global integration is likely to persist, disruptive skirmishes between the US and China will occur with some regularity. Therefore, we suggest that international company strategies today should focus more on risk management related to policy shifts stemming from China’s rise and less on achieving least-cost global supply chains. We present a risk management framework for this purpose.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Scholars and commentators increasingly see China as a global superpower (Anngang 2012; Cao and Paltiel 2015; Fish 2017) and China’s rise is widely understood to be ushering in a new global power distribution (Maher 2016; Shifrinson 2018; Tunsjø 2018; Zeng and Breslin 2016; Xuetong 2019). Footnote 1 China has the world’s second largest economy, trailing only the United States (International Monetary Fund 2020). It was the world’s leading exporter and second largest importer in 2018, the last year for which data were available (World Bank 2020a), and its foreign aid provision and outward foreign direct investment (FDI) have also grown over the last decade (Dreher et al. 2018; Kolstad and Wiig 2012; Wang and Zhao 2017). Accompanying China’s economic rise has been an escalating assertiveness geopolitically (Liao 2018) that reflects China’s growing hard power (Robertson and Sin 2017; Tayloe 2017) and soft power capabilities (Shambaugh 2015).

In short, there is now a strong case to be made that the world has entered an era in which the US and China are approximately equally powerful. This is a marked contrast from the post-World War II era, during which the US dominated in the realms of economy, security, and technology (Ikenberry 2005). China’s emergence as a comparable power to the US raises concerns, since “realist” international relations theory suggests that such a trend will lead to a collapse of globalization as countries reject economic openness in favor of economic nationalism (Mearsheimer 2019). In contrast, we argue that China’s rise does not have to result in reduced international economic integration, and so we present a first research proposition to explore this issue:

China’s rise will not promote de-globalization, though it will lead to jostling for power between the US and China.

There has been a rise of political nationalism in the latter half of the 2010s (Snyder 2019). This has been accompanied by some degree of economic protectionism (Fajgelbaum et al. 2020), raising alarms among business leaders (Edgecliffe-Johnson and Waldmeir 2018). Much has also been made of the ongoing US–China trade war and hostility by US leadership toward the international institutions tasked with supporting economic globalization (Brown and Irwin 2019). However, these concerns may be overblown, as world tariff levels remain low by historical standards (Russ 2019), international trade and investment remain at or near their peaks, and the incoming Biden Administration may be more supportive economic globalization.

In fact, there are significant reasons to suspect that China’s rise will not usher in an era of protectionism and deglobalization. In the analysis that follows, we theorize that a world order in which China and the United States constitute a “G-2” can be conducive to the continuation of global economic integration. Maintaining a relatively open world economy is in the national interests of both of these countries. For that reason, both have committed themselves to international and regional economic agreements to help sustain that outcome. As long as both the US and China see the maintenance of the globalized world as being in their interest, each will adhere to the norms supporting globalization and help those norms to endure. In this sense, as we will explain further below, they will act as “dual hegemons.” As we demonstrate in our analysis, the evidence supports this expectation, such that economic globalization has persisted even as China has become a superpower on (or near) par with the United States.

Even so, China’s rise and the changing global power dynamics that are accompanying it carry significant risks for international business. The new order brings changes to the nature of globalization: Skirmishes between China and the US may disrupt supply chains, threaten new and existing FDI, and include the establishment of new trade barriers. While we do not expect these changes and conflicts to cause a decline in net global integration, we argue that multinational firms need to evaluate and manage the risks that will occur as a result of changes in the nature of globalization.

Just dealing with China has been a risk for foreign businesses, because of the Chinese government’s protectionist tendencies. For example, China requires foreign auto manufacturers to have local partners with at least 50% ownership, as with Volkswagen and GM in their joint ventures with Shanghai Automotive. The government has also shown its disapproval of moving information across borders, as in the case of Amazon Web Services being essentially shut out of the market, and Google and Facebook being severely restricted and banned, respectively. And these policies predate the China–US trade war, which further threatens US-based businesses in China as well as Chinese business going overseas, particularly to the United States. The trade war has resulted in tariffs being imposed on a wide range of products, from steel and aluminum imports into the US to agricultural products exported from the US to China.

While the recent US–China trade tensions are likely to die down, the emerging world order is sure to create more frequent risks for companies engaging in international business, making risk management a priority going forward. A risk management strategy can be sketched broadly by looking at the methods available to MNEs for this purpose. Companies can explore the establishment of production and distribution facilities located outside of the two main protagonist countries. For example, electronics could be assembled in Vietnam or in Thailand rather than only in China; and Mexico or Colombia could be used for additional assembly of electronics, autos, and textiles. Companies also can diversify their business activities such as sales and input purchases into additional countries, again to reduce the dependence on the two main protagonists. A wide range of steps could be taken to mitigate the risks, from the use of insurance contracts for insurable risks to partnering with local companies in the US and China to reduce the liability of foreignness. So, we present a second research proposition:

MNEs need to develop risk management strategies to deal with the US-China competition that will occasionally produce trade barriers and other policy interventions.

The remainder of our analysis proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2, we discuss China’s rise and demonstrate that US and China are approximately equally powerful hegemons. Next, in Sect. 3, we introduce our theory, which posits that global economic integration will persist through an era in which China and the United States are each global superpowers, drawing on theories of international relations. In Sect. 4, we present the evidence so far, which suggests that little shift in global economic engagement can be attributed to China’s rise. In Sect. 5, we discuss in more detail the implications for multinational enterprise (MNE) strategies and we lay out a framework for managing this geopolitical risk. Finally, we note challenges to long-term stability in a world with two global superpowers.

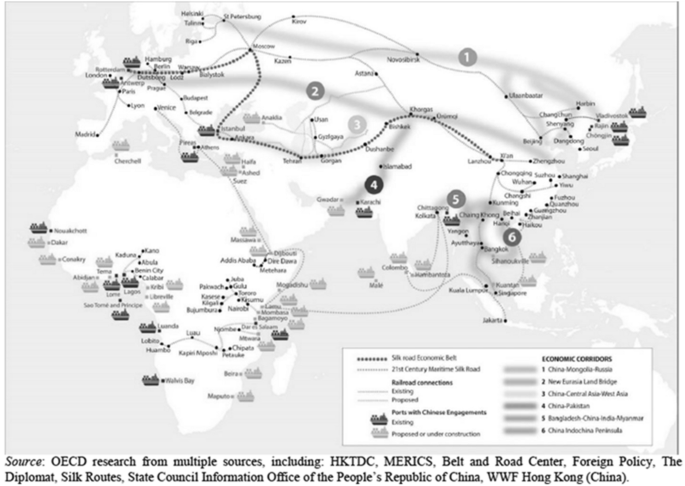

China’s rise is, perhaps, the single most important economic and political phenomenon in the twenty-first century. It has implications for global security (Toje 2018), for international development (Gallagher and Porzecanski 2010; Lin 2018), for global governance (Beeson and Li 2016; Economy 2018), and for human rights (Gamso 2019), among other things. While China’s status in international trade is especially noteworthy, it is also growing by other measures of international power. China’s growing clout in international production and financial markets are evident in terms of its global leadership in overall manufacturing, in the offshore assembly of electronics and textiles, and its growing financial leadership through owning the world’s four largest banks. China is also growing in global leadership through development of new institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and its Belt and Road initiative (Soong 2018). The Belt and Road scope is pictured in Fig. 1.

In terms of total market size, China is nearly as large as the US and much larger than any other country, whether measured in current dollars or in purchasing power parity dollars. In 2019, US GDP was $US 21.4 trillion, while Chinese GDP was $US 14.1 trillion in nominal terms and in purchasing power parity terms, Chinese GDP was $US 27 billion. In terms of company competitiveness, China had 119 Fortune Global 500 companies and the US had 121 in 2019. In terms of innovation, measured as R&D spending in the country, the US led the world by far with spending of $US 581 billion in 2018, while China was second with $US 293 billion, and both countries were far ahead of the third leader, which was Japan at $US 193 billion. Footnote 2 Table 1 presents a comparison of China and the US in terms of some key economic/business indicators.

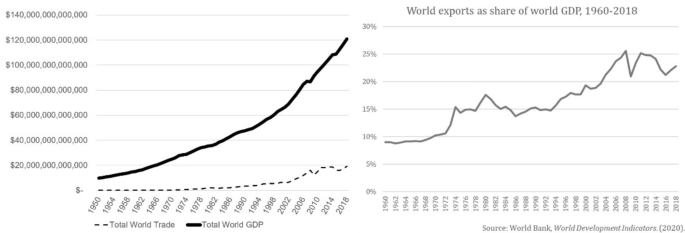

The figure shows that the growth of global trade has plateaued in the 2010s, but that it has not declined and that it remains at or near its peak. This is true whether we look at trade as a share of GDP, as Witt (2019) does, or if we simply look at trade volume independent of GDP. We believe that the latter measure is preferable, insomuch as trade growth may be obscured by faster growth in global GDP, as occurred in the 2014–2016 period. In any case, the figure clarifies that global trade has not declined, suggesting that deglobalization has not been occurring. Footnote 6

The major drop-offs in world trade growth since the early years of the Great Depression in the 1930s have been during World War II, and then, as shown in Fig. 2, during the early 1980s emerging market debt crisis, as well as the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis, a global economic slowdown in 2016, and most recently during the Coronavirus crisis of 2020 (not shown). These events each had short-term impacts on globalization, but they did not lead to a sustained reduction in global trade (Coronavirus notwithstanding).

The 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis illustrates this point and, in the process, offers support for our dual hegemonic stability theory framework. Caused by a malfunction of the US financial system, in which banks and investors overexposed themselves to the real estate loan market and related derivatives, this crisis spread worldwide and caused a recession in many countries. Globalization did indeed decline for that brief period during the crisis. However, this decline proved short-lived, as the US government implemented policies to bolster the global financial system, while China began lending more money to countries around the world. Consistent with dual hegemonic stability, the two global leaders each provided global public goods that prevented what might otherwise have been a dramatic decline in globalization, akin to the one that occurred in the Great Depression.

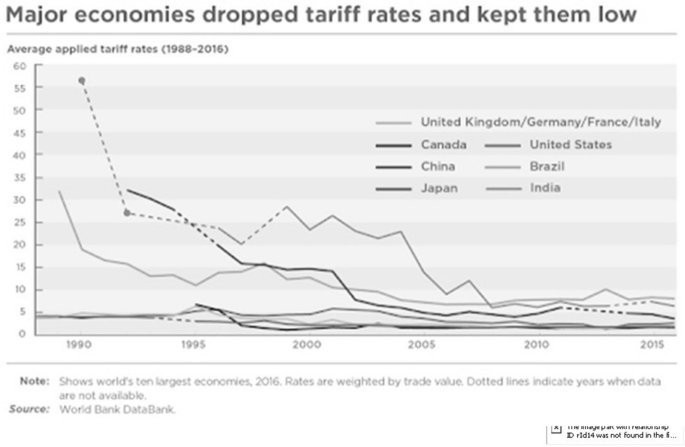

The trend in trade regulation over time is similarly at odds with the deglobalization narrative. Looking at average tariffs of major trading countries, it is evident in Fig. 3 that tariff barriers have continued to fall, from an already low level, since China joined the WTO in 2001.

Non-tariff barriers to international trade, such as import quotas and subsidization of domestic firms to fend off imports, as well as subsidization of exports, have also remained low during the twenty-first century.

While tariffs have decreased steadily overall, there have been exceptions. The US continues to impose restrictions on steel and auto imports, as has frequently been done since Lyndon Johnson imposed steel import quotas in 1969. Ronald Reagan imposed restrictive policies in 1981 (on autos) and 1984 (on steel). Subsequent US Presidents, from George W. Bush (in 2002) to Barack Obama (in 2015) have restricted steel imports with tariffs or quotas, often as a result of claims that foreign governments were unfairly subsidizing their steel exports. These examples suggest that the Trump Administration’s protectionism is not out of line with US policy in the past, contrary to suggestions that the Administration is leading a decline of the global economic order (Walt 2016). Of course, the Trump Administration has implemented its share of protectionism, such as the recent ban on Huawei from selling its telecom equipment in the United States, based on a claim that Huawei was supplying or could supply information about users of the telecom system to the Chinese military (Swanson 2020).

For its part, China also restricts auto imports with high tariffs and subsidies for domestic producers (including subsidiaries of foreign automakers). China also keeps foreign firms out of what they consider sensitive industries such as telecommunications, and they limit foreign financial services firms to a tiny market share in China. China restricts imports of several agricultural products, such as wheat and rice—just as the United States has done for decades. In short, while both countries have exceptions to a free trade policy, over half of the products imported into both countries enter without restrictions, with an overall average tariff of 1.6% in the US and 3.4% in China in 2019 (United States Trade Representative 2020; World Bank 2020a).

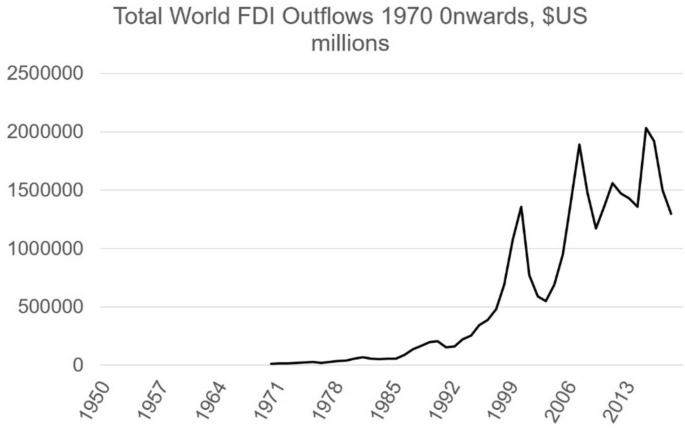

Considering other measures of economic openness, FDI is often seen as an indicator of countries’ willingness to allow foreign business to operate locally. The growth of FDI after World War II has been more rapid than growth of GDP for most of the period. As shown in Fig. 4, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2009 was accompanied by a major downturn in FDI, and since then the growth of this investment has been volatile, though still positive overall. The key point with respect to globalization is that FDI has remained at or near its peak in the years since China emerged as a global power on-or-near par with the US.

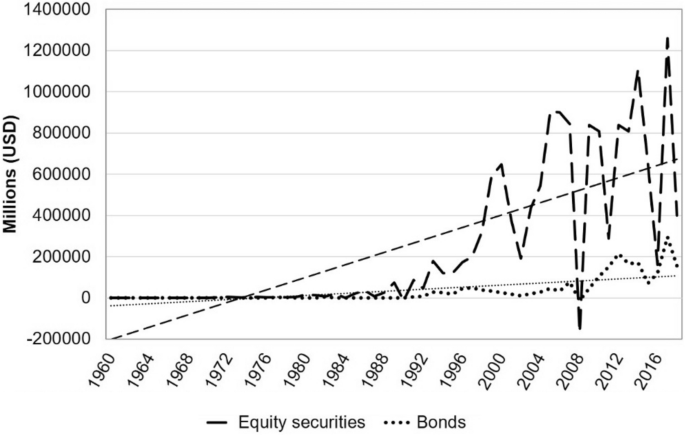

Likewise, global financial flows such as international portfolio investment and foreign exchange transactions have trended upward, albeit with considerable volatility and with a decline during the Global Financial Crisis. Foreign exchange transactions, mainly in London and New York, exceeded $6 trillion per day in 2019 compared with $1.2 trillion in 2001 (Bank for International Settlements 2019). Global portfolio investment grew at an average rate of 44% per year during the 2010s, but it has been very volatile, as shown in Fig. 5. It is clear that globalization has not declined by these financial measures.

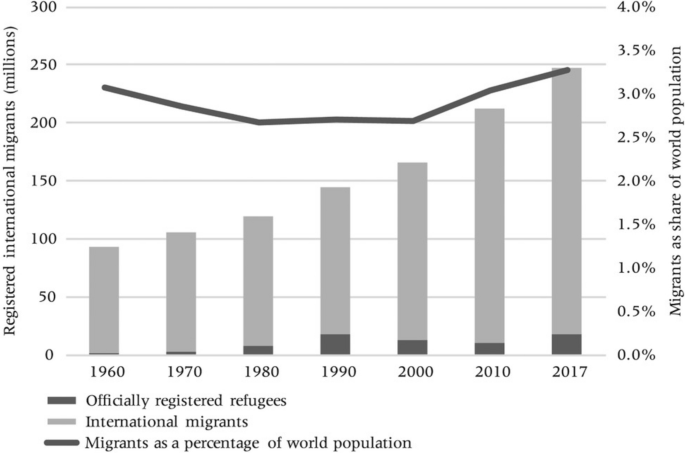

International immigration flows are another measure of economic openness, involving people as the factor that crosses borders. People and capital are generally viewed as the two mobile factors of production, while land is not. And final products and services also may or may not be mobile, as measured by trade flows. It is clear in Fig. 6 that global migration flows have not decreased during the 2010s, but rather they show an increasing rate since the turn of the century.

The evidence presented in this section contests the deglobalization narrative, showing instead that the global flows of products, money, and people have increased in the twenty-first century and remain near their peaks, and supporting our Proposition 1.

While much of the discussion above has focused on macro indicators of international openness and government policies, it all relates to business, mostly to international business. Our principal measure of openness is the amount of trade and investment taking place, and of course it is companies that are carrying out those exports, imports and investments. International bank lending and foreign exchange are mainly carried out by multinational banks, operating principally in London and New York. Footnote 7 Likewise, some international movement of people occurs within multinational firms. These indicators all show positive growth trends in the twenty-first Century, even after the Global Financial Crisis.

From a business perspective, dual hegemonic stability means that countries will maintain an open market environment of the sort that has been demonstrated to attract FDI and also international trade (Ahlquist 2006; Büthe and Milner 2008; Gamso and Grosse 2020). In this context, global companies will continue to engage in trade and investment around the world and do not need to dramatically reorient themselves in response to, or in anticipation of, a wave of tariff hikes or other non-tariff barriers. Supply chains can continue to function and may even deepen as China’s Belt and Road projects bring more countries into the globalized economy. Companies around the world can also expect both China and the US to remain largely open to global business, with positive implications for those firms that are interested in expanding into these markets. Of course, globalization creates losers as well as winners, and our analysis suggests that import-competing companies will not see their fortunes improve in a world of dual hegemonic stability.

That said, US–China skirmishing to build greater economic and political power will produce some policy changes that do constrain firms. Economic issues such as ‘unfair’ trade restrictions on both sides can lead to higher-cost exports if new tariffs are imposed on specific products, even though tariff barriers overall are quite low in both countries. Specific restrictions, as the US has imposed on auto and steel imports from several countries on and off over the past six decades, do raise significant barriers in those sectors. Likewise, China’s refusal to allow foreign telecom companies to provide various services in China, and precluding trans-border transfer of information from China, severely restrict leading US companies in that sector. Chinese government subsidization of state-owned companies in many sectors enables them to compete overseas with an advantage that is difficult to measure and restrain, although it is possible to deal with this challenge through the WTO.

Multinational firms interested in operating in China will continue to have to deal with the restrictions there in sectors such as automobiles, financial services, telecommunications, electric power and operation of any business that requires cross-border transmission of customer information. Constraints there have hobbled the businesses of Google, Facebook, and Amazon Web Services. Auto companies since the 1980s have faced the requirement to operate only with a joint venture partner that owns at least 50% of the company in China. This last point suggests that a strategy for other kinds of firms may be to use a joint venture partner to avoid potential limitations that the government might impose (Zhu and Sardana 2020). And from the opposite perspective, at least for Chinese SOEs, their performance has been better when they have foreign investors involved, such as SAIC with GM and Volkswagen and foreign listings that attract portfolio investors (Zhu et al. 2019).

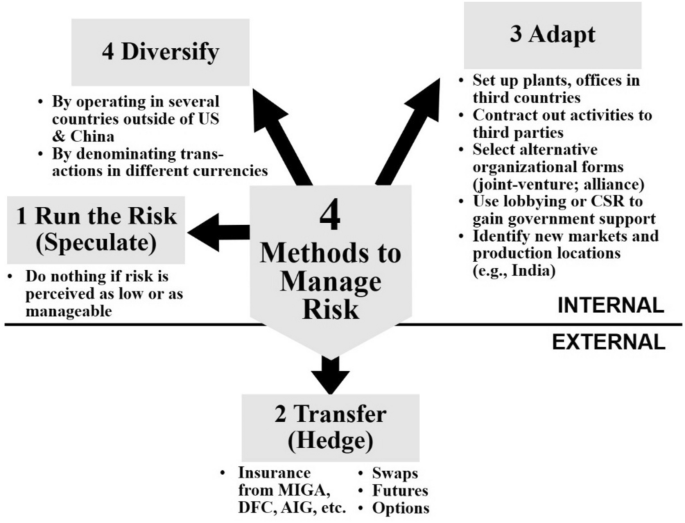

To deal more comprehensively with these risks, we suggest a geopolitical risk management framework within which companies can design strategies to reduce the potential negative impacts of US–China government decisions. The framework is depicted in Fig. 7.

The framework points out four categories of responses to geopolitical risks. First is to simply run the risk when it is perceived to be low or manageable. This strategy will be useful for companies that are not exposed to business activity in the US or China, or for companies that operate only domestically in the US or China. For example, European firms that operate hotels, restaurants, local professional services, and other businesses that are highly local can likely avoid the risk. The more local or regional the business and the supply chain, the more likely that the avoidance strategy can serve well.

Another aspect of this avoidance strategy to deal with US–China conflict suggests that companies should look to avoid putting their business in one of the risky countries, if that risk indeed is very significant for the particular firm or industry (e.g., US defense contractors staying away from Chinese operations, and Chinese companies such as Huawei, TikTok and other Internet companies that could transfer US information to the Chinese military staying away from the US). Many times this is not possible, but when the US-based or Chinese firm can operate in other countries, this can help reduce their bilateral risk.

A second category of response to geopolitical risk is to transfer it to a third party. Insurance is the most common mechanism to accomplish this goal. A political risk insurance policy for a US company from the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) can insure its business in an emerging market against political violence including terrorism, currency inconvertibility and government interference in the firm’s business activities, including expropriation. Similar policies are available from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) in the World Bank group for companies from any member country operating in an emerging market. Private sector insurance policies against political risk are available from companies such as AIG and Zurich Insurance. This category of response could serve the interests of companies that require significant capital investment in facilities in the host country, such as manufacturing companies, hotels, mining companies, and agricultural companies.

Additional means of transferring geopolitical risks to third parties include measures for guaranteeing delivery of a product that may be a part of a company’s supply chain. For example, if oil is needed for the company’s business, (deliverable) futures contracts exist that guarantee a price and the delivery of a specified quantity of oil at a particular future date (e.g., for 1000 barrels per contract at the New York Mercantile Exchange). Similar contracts exist for some other commodities and at some other exchanges as well. Options contracts and swaps for commodities provide additional sources of protection against the risk of breakdowns in a supply chain.

A third strategy dimension is to adapt the company’s business to deal with the risk. This strategy includes setting up plants or offices or other facilities in countries other than China or the US to avoid the direct threat of government intervention. Footnote 8 A company such as Apple can contract out with other companies to provide components for their iPhones and even assembly of those phones, as Apple has done for many years. If key suppliers are in the US or China, then Apple can look to providers in third countries. For any company, if China is the location of production facilities, then adaptation could involve moving to another emerging market in Asia, from Vietnam and Thailand to India.

Chinese firms interested in operating in the US are likely to find more constraints in the way that Huawei and ZTE have experienced in telecommunications equipment and TikTok is experiencing in online video sharing. National security concerns easily could be extended to other sectors, from agricultural products to pharmaceuticals. A Chinese company in many industries would be best served by adapting its business via operating with a US partner, and maybe even operating through a subsidiary in another country such as the UK or maybe Dubai/UAE or the Cayman Islands. Populist pressures as well as national security concerns will likely make it more difficult for a range of Chinese companies to enter the US in the future.

Adapting the company’s business financially may also be beneficial, for example, by taking on local debt in the country where local assets are exposed to risk. Just balancing accounts payable and receivable for a western company in China or a Chinese company in the US could limit the exposure of assets to some extent. Broadly speaking, building up local liabilities where local assets are at risk will help to protect the company.

Many additional possibilities exist to adapt the company’s business activities so that geopolitical risk can be reduced. For both US-based and Chinese companies, finding a joint venture partner in the other country may reduce the risk of negative government policy changes toward that company (Johns and Wellhausen 2016), as might working with an intergovernmental organization such as the World Bank (Gamso and Nelson 2019). For European or emerging market-based companies, finding production locations outside of the US and China can reduce the risk, as can looking to additional markets in other countries such as the EU, India, and other large economies. Aiming directly at the government of China or the US to curry favor, through corporate social responsibility programs (Darendeli and Hill 2016) or just lobbying (Keillor et al. 2005) can also be useful tools.

The fourth and final category of responses is to diversify the company’s business outside of the US and China. This diversification of business activities does not reduce the risk to a particular facility or supply source in the US or China, but it does enable the firm to have alternative(s) in the event of adverse policy moves by either of those governments. So, as with any diversification strategy, moving some activities outside of the two protagonist countries will enable a company to reduce the overall impact of adverse policies on its total business worldwide. An MNE also could aim to denominate more of its business in currencies other than dollars or renminbi, to avoid possible harmful exchange rate changes in response to policies in either the US or China.

This current reality suggests that companies should look to diversify their markets and supply chain activities. Already, a significant amount of reshuffling of offshore production in textiles and electronics has seen assembly activities move from China to other countries in Asia such as Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, as well as India (Hufford and Tita 2019). China’s large market remains very attractive to many multinationals, but India’s market has grown faster in several recent years and provides possible diversification opportunities. And on the other side of the Pacific, the US has recently used policies to dissuade companies from dealing with China, so that a strategy of focusing more on Europe, Japan, and non-China emerging markets makes sense as well for multinationals, even though a significant decoupling of the US and Chinese economies seems unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Each of these strategies implies a move to greater emphasis on risk management and less focus on lean supply chains that has dominated in recent years. In fact, multinational firms would be well-served by implementing a range of risk-management tools, as suggested by our Proposition 2 and shown in Fig. 7 and Table 2 in the “Appendix”.

An open global economy does not mean that companies should naive the risks associated with international business in the context of a changing world order. More short-term trade or investment barriers could be implemented, as the US and China use these policies to compete with one another in various areas of international business and international relations. The bilateral jockeying for position in the international system between China and the US will be a feature that firms will need to contend with for the foreseeable future. Additionally, trade and investment diversion stemming from new bilateral and regional economic agreements must be factored into firms’ assessments as they identify suppliers and consider investments.

There are challenges to the long-term persistence of dual hegemonic stability. These include political tensions between the United States and China, the rise of political nationalism around the world, and the COVID 19 pandemic. The first challenge is the emerging tension between the US and Chinese governments. Tensions over China’s economic policies generated a serious trade dispute between the two countries, which has been partially resolved with the 2020 Phase One trade agreement (Setser 2020). These economic tensions are likely to reemerge and other disputes will surely arise as well. If tensions become sufficiently intense, there is a possibility that the countries will engage in a Cold War-type standoff, perhaps leading other countries to trade intensively with one party or the other. As discussed above, we do not see this as a likely outcome, given the membership of China and the US in the WTO, as well as the enormous economic benefits that both countries obtain from allowing the open economic system to operate. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning, as this outcome is seen as likely by some analysts (e.g., Khong 2019).

The second challenge is the rise of political nationalism around the world. In the latter half of the 2010s, nationalist governments came to power in the United States, Brazil, countries of Western Europe, the Philippines, Turkey, and elsewhere (Snyder 2019). China’s government may also be described as nationalistic (Economy 2014), even though it sometimes shows support for global governance (Kastner et al. 2020). Despite some new tariffs, this political nationalism has not led to widespread protectionism, but it has been accompanied by efforts (some successful) to undermine organizations like the WTO (Brown and Irwin 2019). If political nationalism leads to more sustained economic nationalism, particularly from the United States and China, which are the world’s two largest traders, then it may lead to a deterioration of hegemonic stability. This is not currently in the interest of either state, but interests may change in the future.

Military conflict, such as a possible skirmish in the South China Sea, is also conceivable. Any attack by a Chinese ship or plane on a US ship operating in international waters that the Chinese claim as their own could lead to escalation of some sort. Ramped-up military attacks are not likely, but economic sanctions certainly are. This would push each hegemon to raise more economic barriers on the other, and hurt MNE interests. While this is far from a Pearl Harbor or a frontal attack on the other hegemon, still such skirmishes are likely, and their policy implications are something that companies should plan for.

COVID 19 may exacerbate the first two challenges. The virus appears to be worsening relations between the United States and China, at least in the short term (Buckley and Myers 2020). Likewise, there are some indications that COVID 19 is encouraging countries to turn inward, in an effort to increase self-sufficiency (Irwin 2020). However, it is too soon to say how exactly the 2020 pandemic will affect global commerce in the coming years and decades, and there are reasons to suspect that its long-term impacts on globalization will not be severe (O’Neill 2020). Nevertheless, this unprecedented challenge must be acknowledged.

These possibilities notwithstanding, the most likely scenario for world order in the twenty-first century is ongoing economic globalization, led by two states that have persistently supported and benefited from this status quo. Continuing to support globalization is in the best interests of both of these states, and so we expect them each to continue providing global public goods that incentivize global trade and investment. Therefore, contrary to the increasingly common journalistic narrative, globalization should persist for the foreseeable future. Even with a continuation of globalization, companies need to be prepared to deal with bilateral frictions between the US and China, so the four-pronged risk management strategy described above can help them to manage future shocks.

It should be noted that there are dissenting opinions to this emerging conventional wisdom, as some analysts are skeptical of US decline (e.g., Brooks and Wohlforth 2016a, b), others are skeptical of China’s rise (e.g., Lynch 2019), and still others propose that a multipolar world order has emerged (e.g., Mearsheimer 2019).

While one could debate the appropriateness of R&D spending as a measure of innovation, the US-China dual leadership also is evidenced by patents and trademarks granted, and by other measures collected by the World Intellectual Property Organization (2019). While no measure of innovation is complete, the various indicators all point toward US-China leadership.

US-China trade was valued at $578 billion, with a US deficit of $347 billion, in the last year of the Obama administration (2016). US-China trade was valued at $558 billion, with a US deficit of $345 billion, in 2019.

“More Americans than Gallup has seen in a quarter century view foreign trade positively, with 79% calling it "an opportunity for economic growth through increased U.S. exports" (Saad 2020).

This is not to deny the real trade barriers that have been imposed on US-China trade by President Trump since 2017, and the retaliation by China’s government. These restrictions, mainly tariffs, have had some impact on that trade, though it continues fairly similar in volume and value to previous years, with some exceptions.

Of course, this does not take into account the impacts of COVID 19 on global trade.It would be logical to expect Hong Kong, or even Shanghai, to join London and New York as the chief global financial centers. For several reasons, mainly to do with political risk of the Chinese government in Hong Kong, this last center has not (yet) developed on the level of the London or New York.

If the company is changing an existing activity, such as moving production out of China, or contracting production to a third party, then this is adaptation. If the company adds new operations outside of China or the US to deal with this geopolitical risk, then this would be diversification, as discussed in the next category.

We would like to thank Mark Casson and Rob Spich, as well as the editors of MIR, for their very helpful comments on this paper.