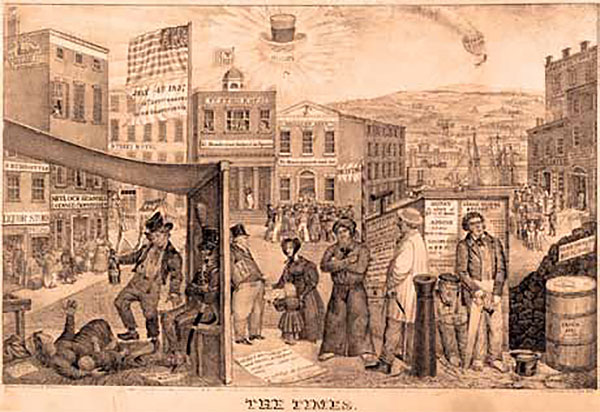

The story of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the national banking system begins in 1863, when the National Currency Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln.

The National Currency Act was a response to the mishmash of local banks, local money, and conflicting regulatory standards that prevailed before the Civil War. Banking systems varied from state to state. Some states required a special act of the legislature before prospective bankers could obtain an operating charter. Other states adopted "free banking," under which charters were granted to all applicants that met established conditions. In such states as Indiana and Tennessee, banks were state-operated and -owned; elsewhere, ownership was vested in public-private partnerships. And in states like Ohio, several of these institutional arrangements were in use at the same time.

The pre-Civil War money supply consisted of various types of gold and silver coins along with paper notes issued in multiple denominations by each of the thousands of individual banks. In theory, holders of notes could return them to the issuer and receive their face value in precious metal. However, especially where state supervision and oversight were weak, banks tended to issue notes beyond their redemption capabilities, which led to bank runs and failures.

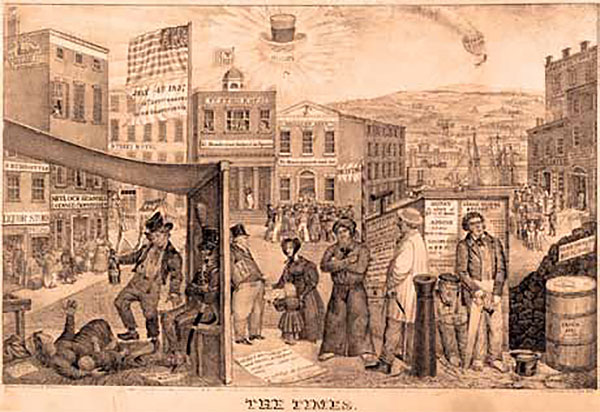

The disorderly pre-Civil War money supply, based on state bank notes, contributed to periodic "panics" and economic hardship (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division).

But the biggest problem with state banking before the Civil War was that it discouraged the development of an integrated national market and a shared national identity. At each destination, long-distance travelers had to convert their bank notes into local money, usually sustaining a loss with each exchange. The cost and inconvenience were significant deterrents to interstate travel and commerce.

Such a fragmented banking and monetary system increased the likelihood that people would think of themselves as citizens of a state or a region rather than citizens of the United States.

Local and sectional loyalties tore the country apart in1861. The National Currency Act of 1863 was part of Congress's attempt to stitch it back together.

The immediate challenge was meeting the costs of a civil war that vastly exceeded anything the government had confronted before. As the war ground on, the challenge of keeping the troops paid and provisioned became a crisis that rivaled the military challenges on the battlefield.

Congress acted on several fronts. Taxes were raised. Assets, especially land, were sold. Fiat currency—the unsecured paper known as green backs—was printed and used to pay the troops and their suppliers. And the government borrowed. But in the face of military reverses that raised doubts about the government's prospects and permanence, bond sales faltered.

One of the purposes of the national banking legislation introduced in December 1862 was to stimulate bond sales and generate a rush of cash for the hard-pressed U.S. Treasury. The legislation would create the first national bank charter. Applicants would have to meet minimum capital standards, pass muster with the system's administrative officer (designated the Comptroller of the Currency), and be willing to buy U.S. bonds to be deposited with the Comptroller as security for the new national currency. Supporters of the legislation promised that tens of millions of dollars would be raised annually for the war effort through such bond sales; in the end, the wartime take amounted to a fraction of that.

Some members of Congress supported the national banking legislation as a simple act of patriotism. But the legislation's leading proponents—President Abraham Lincoln, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, and Ohio Senator John Sherman—saw the legislation not only as a way to tap the North's wealth and win the war but also as a means to assure the future greatness and permanence of the United States.

At the heart of their vision was a safe, sound, and reliable banking and monetary system. The OCC would write uniform rules that would apply to all national banks and send examiners into the banks to make sure those rules were being followed. The national currency itself would be identical except for the name of the issuing bank and the signatures of its officers. The idea behind the system was simple, but the system's impact on commerce, public confidence, and national unity would be profound.

The bill that Lincoln signed into law on February 25, 1863, established the system's basic framework. Because it was passed with relatively little review or debate, the bill was imperfect and incomplete, prompting the first Comptroller, Hugh McCulloch of Indiana, to change and clarify many of its provisions. Congress passed McCulloch's expanded and redrafted version, called the National Banking Act, in June 1864.

McCulloch was in fact an unlikely choice for Comptroller. He had come to Washington in his capacity as president of the state-owned Bank of Indiana to fight against the national banking legislation, which he rightly perceived as a threat to state-chartered banking. Although he had tried to block the system's creation, McCulloch was now determined to be its champion.

McCulloch was an industrious, able administrator. He acquired office space, hired a staff, assisted in the design of the new national bank notes, and arranged for their engraving, printing, and distribution. He personally evaluated applications for bank charters and consoled prospective bankers who were late with their paperwork and the initial installment of their paid-in capital, thus losing out to competitors for the coveted designation of "First National Bank" in the same locality.

McCulloch was keenly aware that his decisions would set standards for years to come. In a letter of advice to bankers in 1863, McCulloch encouraged the pursuit of "a straightforward, upright, legitimate banking business."

"Never be tempted by the prospect of large returns to do anything but what may be properly done" under the law, he advised.

Although the new law allowed both new charters and the conversion of state banks into national ones, McCulloch, as a former state banker, gave preference to the latter, convinced that experienced bank managers were essential to the system's success.

For various reasons, they were slow to take him up on the offer. Some bankers were reluctant to abandon the descriptive, sometimes colorful names their institutions had borne for years, like the Safety Society Bank and the Planters and Drovers Bank, in favor of the dry "First National" and "Second National" nomenclature prescribed by the new law. Bankers also balked at the law's capital requirements, the prospect of tougher federal oversight, and the restrictions on activities that state laws allowed them to conduct, such as real estate lending.

In March 1865, in the face of this reluctance, Congress passed a 10 percent tax on the notes of state banks, signaling its determination that national banks would triumph and the state banks would fade away. And, for a time, they did.